Asian pot growers face sheriff raids, bulldozers in Northern California. They blame racism

BIG SPRINGS, SISKIYOU COUNTY

Sheriff’s Day after day, deputies drive up and down the road outside Steve Griset’s 600-acre farm, pulling over anyone who appears to be hauling water for the thousands of marijuana greenhouses that have taken over the countryside here.

Sheriff’s Day after day, deputies drive up and down the road outside Steve Griset’s 600-acre farm, pulling over anyone who appears to be hauling water for the thousands of marijuana greenhouses that have taken over the countryside here.

Griset has become a target, even though he grows alfalfa. Last year, investigators with the Siskiyou County District Attorney’s Office raided Griset’s house with a search warrant looking for his business records, and the DA followed up with a lawsuit in civil court.

Griset’s alleged transgressions? He was selling water from his well to his pot-farming neighbors, immigrants of Hmong descent who have helped turn this sparsely populated, volcanic-soiled section of California into a major source of cannabis production.

After someone entered Griset’s property during the night and damaged his well pump with an ax earlier this month, it became clear he was caught in an escalating conflict in Siskiyou County that has raised fevered complaints about anti-Asian harassment, environmental destruction, and unequal enforcement of California’s complex cannabis laws.

“They’re around my ranch almost all the time,” he said of the sheriff’s department. “It’s really intimidating.”

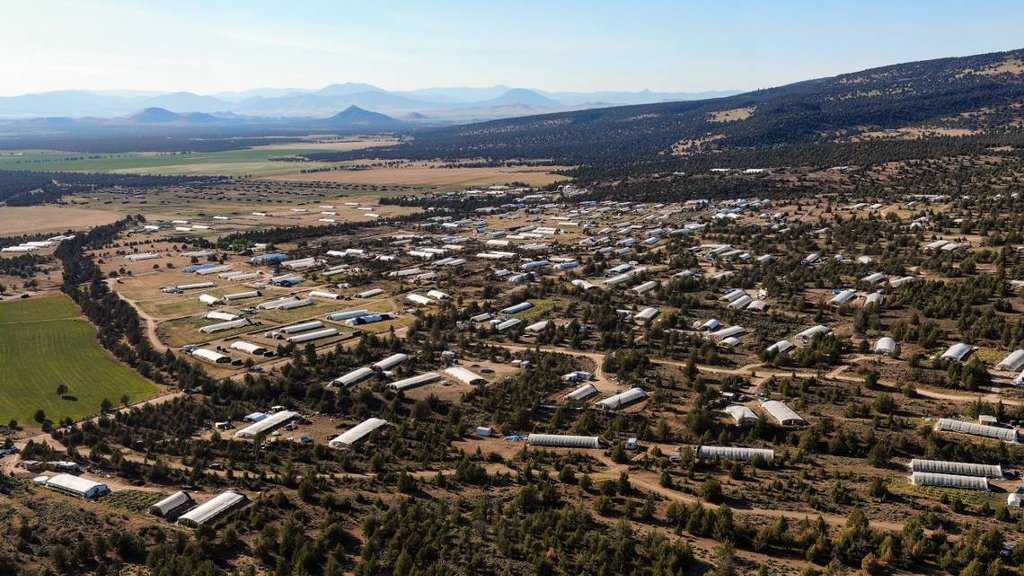

Law enforcement officers are aggressively enforcing ordinances that prohibit well owners from selling and trucking water to pot farms, most of them owned and tended by the farmers of Hmong and Chinese descent. Thousands of their greenhouse have quickly replaced a few square miles of juniper and brush in the Big Springs area in just a few years.

At the same time, deputies are threatening to cite local businesses supplying the cannabis farms with soil, lumber and other materials that amount to “aiding and abetting in the illegal activity,” the sheriff’s office said earlier this month on Facebook.

The sheriff is also recruiting private citizens to operate “heavy equipment, such as dozers and excavators” to bulldoze greenhouses to combat what the sheriff on Facebook calls the “illegal Commercial Cannabis Activity plaguing our county.”

The pot growers believe they are being targeted because of their race, seizing on the “Stop Asian Hate” rallying cry following a rash of hate crimes. They’ve protested by the hundreds in front of the courthouse in Yreka, the county seat, and they’re working with their attorneys, they say, to file a federal civil rights lawsuit against the county.

“We came here just to make a living,” said Peter Thao, a former Sacramento mortuary owner who serves as a spokesman for the Hmong community in Big Springs. “And we feel that we are being targeted.”

The growers argue that if you drive down secluded rural roads in Siskiyou County, you’ll find large pot grows tended by white people. They ask: Why are only Asians being singled out?

Deputies, Thao said, “come out here and do horrible things and have treated these people horribly. It is totally unjustified.”

Local officials fiercely dispute the charge that their actions are racially motivated. Instead, they said they’re enforcing local laws prohibiting commercial pot farming and addressing the proliferation of greenhouses and grow sites filled with run-down camp trailers, ramshackle dwellings and living quarters often without power, water and sewage service that have overwhelmed Big Springs and a few other areas around the county.

The marijuana grows in Big Springs are visible from miles away in the lava rock hills below Mount Shasta, a shocking sight for many longtime residents and a reminder that the marijuana industry now has a major foothold in this county. They say the cannabis farms have scarred the environment, sucked precious groundwater from the region’s supply, and led to violence.

“This is another way to try to enforce the law,” said Siskiyou County District Attorney Kirk Andrus. “It has absolutely nothing to do with race. And that I even have to say that really makes me angry.”

For years, Siskiyou County law enforcement officials have said the growers in the area have ties to organized crime — an allegation the growers dispute.

Two growers allegedly tried to bribe the former sheriff, Jon Lopey, for $1 million in 2017 when he was wearing a wire. The siblings, Chi Meng Yang and Gaosheng Laitinen, remain in federal custody. They’ve pleaded not guilty, and their trial is scheduled for August in Sacramento.

The battle in Siskiyou County illustrates how in some parts of California, the legalization of marijuana has failed to bring the cannabis industry fully out of the shadows. In these places, large-scale marijuana farming remains a criminal enterprise.

Proposition 64, approved in 2016, allows local governments to ban commercial cannabis operations if they choose. Some conservative rural counties, like Siskiyou, have chosen not to allow any commercial cannabis operations. Siskiyou limits the number of pot plants on a property to 12. It has banned outdoor grows.

Since October, the sheriff’s office has destroyed nearly 138,000 plants, seized at least 21,738 pounds of processed marijuana and $601,476 in cash from the grows in Big Springs. Deputies have cited or arrested 83 people. As California decriminalizes cannabis, county officials no longer can hold the growers in the local jail for very long.

“It’s not like it used to be,” said newly appointed Sheriff Jeremiah LaRue. “They plead guilty and pay the fine, and then (they’re) right back to doing what they’re doing.”

Siskiyou County, instead, is going after marijuana farmers by aggressive regulation of the most important natural resource in the state: water.

Alfalfa and hay farmer Griset thought he’d never have to worry about water again when he sold his farm a few years ago in the San Joaquin Valley and bought a new one in Siskiyou County. His new place has a well with water to spare, and the political climate seemed favorable, too.

Siskiyou, after all, is the birthplace of the State of Jefferson movement to secede from liberal California and form a new conservative state. Here, property and water rights supposedly reign supreme. Now, he’s not so sure.

“The State of Jefferson is the state of ordinances,” Griset said, “and it’s just absolutely mind-boggling.”

Around a dozen water trucks sat parked and empty earlier this month under and around a pole barn on Griset’s property, a few feet from the filling hoses connected to his well pump. Someone spray-painted “No steal” on a rock at the water truck filling station.

LURE OF CHEAP LAND AND ROOM TO GROW

Lee, a computer programmer and entrepreneur was among the first Hmong to arrive in Siskiyou County from Fresno in 2015. Lee was responsible for many of the real estate transactions in Big Springs.

He told The Bee in 2017 that he and other Hmong men and women fell in love with Siskiyou County because its terrain reminded them of the mountains of Laos, where the Hmong lived and many farmed opium for generations. Years after the U.S. pulled out of Vietnam, thousands of Hmong refugees who fought on America’s behalf were allowed to immigrate to the United States, with many of them settling in California’s Central Valley.

In interviews, some Hmong marijuana farmers said they were drawn to the rural lifestyle.

“My parents have no kids no more. They want to be out here like back in the days, because, you know, no stress. It’s just farming, camping-type style,” said one Hmong grower, a 40-year-old man who has a wife, school-age kids and a new baby back home in Merced. “So they actually move out here and build themselves and live out here.”

Most of the younger generation Hmong, like him, only tend to the grows seasonally, he said.

In Siskiyou County, the lure of cheap property and piles of tax-free cash from cannabis has outweighed the risk of a crackdown from local authorities. In just a few square miles of the craggy volcanic hills north of Mount Shasta, a land rush has been underway since 2015. Parcels originally sold for as cheap as a few hundred dollars an acre.

Swimming pools and large portable tanks supply many of the grows, with well water delivered by tanker truck.

LaRue, the sheriff, estimates there are now 5,000 to 6,000 greenhouses growing pot in the Big Springs area alone. Almost all of the greenhouses have shown up within the last three years. He said as many as 4,000 to 8,000 people may be tending them.

If so, that represents a major uncounted demographic for Siskiyou County, with an official population of just 44,000. Census figures show the county is 86% white and 1.6% Asian. Latinos and a large population of the Karuk Tribe, which has fought its own battles over water and white settlement, make up most of the rest of the county’s population.

The Hmong growers said cutting off their water has had an immediate and devastating effect on their operations and the multigenerational families who work here.

“Our plants are dying, our chickens dying, our animals are dying,” said the Hmong grower.

He asked that he not be identified out of fear that if he spoke critically of the county his parcels would be targeted for a “chop” — what he called the law enforcement raids that happen in Mount Shasta Vista, a 1,641-lot subdivision that’s been converted into cannabis farms run primarily by Hmong families.

He took a Sacramento Bee reporter into the subdivision as deputies dismantled one of his neighbor’s greenhouses and destroyed what appeared to be hundreds of plants.

The next week, two dozen law enforcement officers raided properties tended by Chinese immigrant farmers on the hillsides on the other side of County Road A-12, the main highway through Big Springs. They eradicated 50,861 plants and bulldozers tore down 143 greenhouses, LaRue said.

The grower said many in the area would prefer not to rely on water trucks, but the county won’t issue well permits.

Now, with the latest crackdown, even the portable toilet companies are reluctant to come out to service the toilets placed at many parcels out of fear they’ll be hit with “aiding and abetting” charges.

“They couldn’t even come in and come clean the toilets no more, and they say the sheriff’s f------ with them so they’re not supposed to do that,” the grower said.

LaRue, the sheriff, said that’s not true. He said it’s only considered a crime if a delivery or a service is clearly connected to a cannabis operation.

“If you deliver a pizza out there, which isn’t happening, but just say it was, that’s not aiding and abetting commercial cannabis activity,” LaRue said. “But when you show up with, you know, with thousands of dollars of soil … you’re a part of this.”

Earlier this month, two deputies pulled over Brandon Fawaz’s truck hauling a load of fertilizer on the road leading to the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision. He said he wasn’t delivering to the cannabis operations, and he wasn’t cited.

He said business owners like him should not have to “live in fear” that they’ll be arrested or cited if they end up driving down the wrong road.

“The cannabis laws are confusing,” he said. “I don’t know who’s a legal grower and who’s not.”

TRUCK AFTER TRUCK HAULING WATER FOR CANNABIS GROWS

In the beginning, the county officials tried to crack down by doing raids on the grows and chopping down and seizing their harvest, but they say they quickly popped back up again, often within days.

“The same day, we’ve had them replant,” said LaRue, the sheriff who was appointed last year.

Last summer, the county supervisors tried something new: Attacking the growers’ water supply. They passed an ordinance that prohibited local well owners from selling water to marijuana farms. Violators face fines of up to $5,000 a day. Neighbors said it did little to slow the massive lines of water trucks.

“There were 93 water trucks going past my home, in one direction, between 5:30 in the morning and 12 noon,” said Ginger Sammito, who lives near Griset’s property.

Citing California’s drought emergency and after hearing complaints that local residential wells were going dry, the county Board of Supervisors earlier this month took the ban on pot water even further. They prohibited water trucks on certain roads leading to large grow operations, such as County Road A-12 outside Sammito’s and Griset’s properties.

Teams of deputies and California Highway Patrol officers now buzz up and down A-12 and other heavily trafficked cannabis roads looking for violators. On A-12, deputies have stopped at least 75 people since the supervisors passed the ordinance on May 4.

So far, deputies impounded at least four vehicles for ordinance violations, and issued 11 citations, though LaRue said some of the citations were for marijuana possession or traffic violations and weren’t related to the ordinance.

Sammito, the neighbor who counted all the water trucks driving past her Big Springs home, said her well’s water line has dropped by several feet, and it’s increasingly filled with sediment.

She said she’s one of the lucky ones.

“There’s 31 wells that went dry, including our fire department’s. We currently have no fire service in this area,” said Sammito, a retired statistician who worked for the U.S. Forest Service.

The Hmong growers and Griset dispute that their operations are having a substantial impact on the region’s groundwater. They argue that pumping water into trucks for cannabis grows represents just a fraction of the amount pumped by hay and alfalfa farmers in the area.

“They honestly believe that three of these drain the aquifer, and their wells went dry,” Griset said, holding up one of the small pipes that connect hoses to water trucks. “And they even protested against this.”

The county is in the process of tallying its groundwater resources and pumping amounts to comply with state law enacted in the last drought that seeks to regulate groundwater use for the first time. The state considers the Shasta River valley north of Mount Shasta a “medium priority basin” that isn’t critically over-drafted. Big Springs sits on its eastern boundary.

The sheriff estimates that it would take almost 30 acre-feet per day of water to grow what county officials estimate to be the 2 million marijuana plants being tended across Siskiyou County. An acre-foot is enough to flood an acre of land one foot deep with water — or 325,851 gallons.

At the same time, county officials said that at least 388 agricultural production wells pump around 38,000 to 40,000 acre-feet each year for irrigated agriculture from the Shasta groundwater basin alone, with most of that going to alfalfa. The rate of pumping for traditional agriculture has increased by about 40% since the 1990s.

If pot was consuming 30 acre-feet a day over a year, it would be an additional 10,950-acre-foot strain on the county’s groundwater supplies.

But Griset said those numbers are wildly out of line with the reality on the ground. It would take more than 2,100 water trucks to carry that amount each day, since a truck can typically only haul up to 4,500 gallons at time.

Griset estimates that he only pumped about 50 acre-feet into trucks over the course of an entire year — and he said he was by far the biggest supplier of water to the growers in his area, filling as many as 150 trucks in a day. (He declined to say how much the growers are paying him for water.)

But he said he can see why his neighbors blame the trucks for wells drying up instead of the irrigation sprinklers like his that this time of year are blasting water nonstop on the Shasta Valley’s hay and alfalfa fields.

“The line just kept getting longer and longer,” he said. “Pretty soon there’s like 50 trucks lined up to get water. They have to wait three hours to four hours. Local people look and they go, ‘Oh my God, look at all those water trucks and how much water is going out.’ ”

‘TYRANNY THAT’S OUT THERE’

Andrus, the district attorney, said protecting groundwater might be a side benefit of enforcing the county’s ordinance, but it’s not the intent.

“We’re not pretending that this is something that’s trying to regulate anything except for water being used for cannabis,” he said. “It’s a way to enforce California’s and Siskyiou’s cannabis laws. That’s what it’s for. It is not designed to protect the aquifer, or the groundwater.”

Andrus has since sued Griset and another farmer for violating the rules. The defendants are fighting the lawsuits in civil court. Griset has not been charged with a crime following the September search warrant raid at his farmhouse.

LaRue said the crime problem has only gotten worse in Big Springs over the last few years as criminal operations have taken over and put in industrial grow houses. Investigators suspect human trafficking with people being forced to tend grows against their will, LaRue said.

“We believe there’s people in this community that don’t want to be here that are being kind of forced to be here,” he said.

Siskiyou officials say they’ve had little help from California officials to address the problem.

“How do you even help defend them against the tyranny that’s out there without getting people to come in and help?” LaRue said, sitting in a sheriff’s office conference room in Yreka. A Thin Blue Line flag was on the wall.

A sheriff’s office list of its calls from last year in Big Springs shows deputies responding to four assaults, four reports of child abuse, nine burglary calls and 13 calls for disturbing the peace. They seized 21 guns since October.

There have been five murders in the Mount Shasta Vista area in Big Springs in the last three years, LaRue said. Before 2015, the sheriff’s detectives investigated one to two homicides a year in the sprawling county that has a land mass nearly the size of Connecticut and Rhode Island combined.

“That gang stuff, the turf war, if you will, out there that’s got to end because people are getting killed. And it’s not worth it. It didn’t matter what they’re growing. If they’re growing tomatoes, we’d be doing the same thing. It’s just sad what it’s become.”

The most recent murder culminated with the arrest last month of Alvin Thao, 26, for the August murder of 52-year-old Shao H. Huang in the Mount Shasta Vista subdivision. Thao also has been charged with robbery and kidnapping.

Other crimes never get reported, LaRue said.

“We’ve gotten reports of people showing up at the Mayten Store that are hosing off, they’re bleeding, looking like they got stabbed,” LaRue said. “We don’t hear about that.”

ASIAN FARMERS SAY: ‘WE’RE NOT CARTEL’

Mouying Lee, the computer programmer and entrepreneur who was among the first Hmong to settle in Big Springs, was among those who filed an unsuccessful civil rights lawsuit against the sheriff’s office alleging Hmong were harassed by local law enforcement officers as state officials investigated claims of voter fraud. Lee had sought to challenge the county’s marijuana ban by collecting signatures for a countywide vote in 2016.

The county argued that deputies only provided security for the state officials investigating complaints that dozens of people from out of town had registered to vote at vacant lots or at Lee’s address.

In October, Andrus’ office charged Lee with 78 counts of money laundering, falsifying tax returns and cannabis cultivation. Judge Karen Dixon ordered him held on $3 million bail, arguing he was a flight risk because he has family in Thailand.

In court, Lee’s attorney argued he is an American citizen, with close ties to the community and not a flight risk. They said his bail was ridiculously high for someone accused of a nonviolent crime. They argued his continued incarceration put Lee at risk of contracting the coronavirus in jail and ran counter to recent state reforms that seek to end the cycle of keeping non-violent offenders — most of them minorities — in jails and prisons for minor drug crimes.

The issue came to a head earlier this month in Dixon’s court.

Lee’s attorneys argued that because authorities had seized Lee’s assets, he had no way of posting bail.

The district attorney argued that Lee continued to make tens of thousands of dollars from rents on his grow sites, and that he had more than $750,000 in assets that detectives couldn’t account for.

After a daylong hearing, Dixon agreed to free Lee, but she imposed numerous conditions on his release. He has to wear a GPS ankle monitor, he forfeited his expired passport, the DA put him on the so-called federal “no-fly list,” and he was ordered to make sure there’s no cannabis production on any of the properties under his name. He’s not allowed to visit them.

He also is required to allow county officials to place meters on any source of water on property he owns.

To local authorities, Lee is a ringleader of a massive criminal enterprise, cashing in on rent and the proceeds from drugs grown on the dozens of properties he owns or manages in Big Springs.

But to the Hmong growers, he’s a respected community leader.

The day of Lee’s release, dozens of Hmong families gathered under Griset’s pole barn a few feet from his well.

Earlier that day, they tried to hold the gathering at a park in the nearby city of Weed, with some of them carrying American flags and flowers. But they were forced to move after a local official drove down and told them they couldn’t gather there because they didn’t have a permit.

At the barn, an elderly Hmong woman chanted and sang in her native language into a microphone as around 200 others sipped Bud Lights and piled rice and rich stews onto paper plates from a long buffet table.

As the gathering was winding down, on the dirt road leading up to the barn, two deputies pulled over Fawaz, the fertilizer hauler.

Thao, the former Sacramento mortuary owner serving as the Hmong spokesman, said his people aren’t leaving, despite the risks of living without water.

“If the sheriff continues to practice this water issue by taking away from these people, they’re not gonna go home. I know that. And it’s gonna get worse. It’s going to be televised not just locally, nationally and possibly internationally.”

Thao said LaRue, the new sheriff, has made no effort to speak with the Hmong clan elders, who in that culture settle disputes and set policy.

“If they want to meet with us, we’re more than happy,” he said. “We’re not cartel. We’re not afraid and ashamed to meet with them.”

LaRue said that he’s reached out directly to the growers, including Lee.

LaRue approached a group of them at the entrance to Mount Shasta Vista, soon after the water truck ordinance passed. He said he and a sergeant were surrounded by “very angry folks.”

“We were mainly getting screamed at and they blocked us in,” LaRue said. “So we just left the area and got out of there.” The following week, LaRue said he gave his number to one of the growers.

“I said, ‘Hey, give this to whoever’s in charge out there,’ and I said, ‘Have them call me,’ ” he said.

But, quietly, some of the growers acknowledge that things are getting out of hand, as an influx of Chinese newcomers have bulldozed hillsides to build even more massive greenhouses.

“They f------ the shit up for everyone,” said the grower from Merced who asked that his name not be used. “We do blame them a little bit, but, you know, it’s just what it is. And I think the sheriff, they just got tired of us. But, you know, at the end of the day, we still want our rights. It’s a private property, and we can drive in here with our water trucks ... Don’t f------ just make up some rules and f------ target straight us.”

Griset, the farmer who’d been selling his water to the Hmong, believes he’s doing nothing wrong, but he also admits he feels increasingly uncomfortable with the long line of greenhouses that are creeping closer along the hills toward the edge of his hay fields.

“They came in with bulldozers and just cleared areas and just put solid greenhouses. And I don’t even want my water going to any of that,” Griset said. “We just watched them build and build and build and build every year, and I go, ‘Oh my God, there is not gonna be enough water for these people. This is gonna be crazy. I don’t want to do this.’ ”

Comments

Post a Comment